Well, we did.

When in Rome

Modern warehouses are the successors of the granaries that early civilizations built to store surplus food to help people survive long winters or famine, but leave it to Ancient Rome to go big or go home.

About 2,200 years ago, the Romans—who were still in the midst of a conquering spree—completed the Horrea Galbae, which closely resembled the large structures we know today as a place for the storage and retrieval of goods. It was a massive complex of warehouses near the Tiber River containing more than 140 rooms and covering approximately 225,000 square feet. It was used to store the public’s grain supply, as well as goods like imported olive oil, wine, food, and clothing.

The decision to build such an enormous facility so close the river was deliberate: Roman ships packed with the spoils of conquest sailed into port to unload their treasures, and it was a short “last-mile” chariot haul to storage.

Ports were the lifeblood of the Roman Empire. Warehouses would become a hallmark of this system, as seafaring explorers from Europe established new trade routes, bringing back exotic goods to buildings located at their home ports for easy offloading.

Rule, Britania

As for the word “warehouse,” the first known use dates back to Britain in the 1300s as “a structure or room for the storage of merchandise or commodities.” In other words, a house to store your wares—with “wares” increasingly meaning manufactured goods like glassware and ceramics.

In the centuries that followed, as England ruled the waves and continued to extend its reach, warehouses would pop up in port cities all over Europe and the world. Larger, faster ships enabled the establishment of global trade routes, and these ports and warehouses became the heartbeat of civilization—pumping commerce from the coast to the interior.

The word “warehouse” itself became a verb in the late 1700s during the Industrial Revolution when the idea of “warehousing” as a business practice came into fashion, as in “Go ahead and warehouse those crates of dishes.”

With the invention of the steam engine and textile machines, mass production in factories took off like a rocket, which in turn led to the need for the increased capacity to store those goods prior to domestic distribution or export overseas.

Rail to Retail

If warehouses were the heartbeat of commerce, early railroads were the arteries that allowed the flow of merchandise to cities and towns inland. That led to even more warehouses (or depots) being built at transportation hubs, giving manufacturers a way to move their goods faster and farther than ever before, opening new markets and transforming towns into cities.

The late 1800s saw the dawn of the Second Industrial Revolution, with electricity powering another manufacturing expansion. It brought us the light bulb, the telephone, and the internal combustion engine. The invention of the automobile kick-started another revolution in long and short-haul transportation and commerce, and the world was further transformed by undersea cables and radio waves that linked countries and continents in a global economy. So, throughout history, we have created more and more wares and more and more ways to distribute them—with warehouses serving as crucial links in those distribution chains. And the longer and more complex those chains became, the need for more warehouses increased in proportion, and continues to grow today.

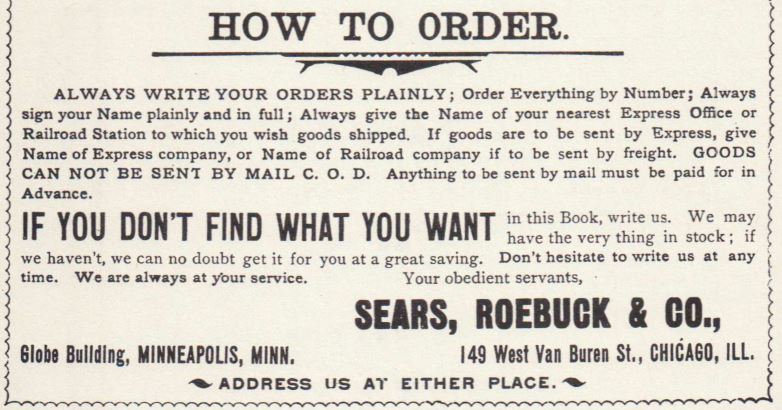

One of the first businesses to realize the potential of this growing infrastructure was mail-order company Sears, Roebuck & Co., which was the Amazon.com of its time. The Sears catalog contained thousands of items, from clothing and toys to appliances, medical supplies, and even house kits. Much of this merchandise was housed in a massive distribution complex in Chicago covering a whopping 3 million square feet. And all year long, order forms filled out by hand listing what items and in what quantity, size, color or style customers wanted to purchase arrived by mail.

Needless to say, the workers fulfilling those orders in the months leading up to Christmas would have welcomed any form of automation as they searched the endless aisles during Chicago’s legendary winters. And just imagine how many mistakes were made when trying to figure out orders with transposed catalog numbers or poor handwriting. Surely there had to be a better way.

And there was.

Coming up next week—A Brief History of Warehouses: Part II. Modern manufacturing and the rise of automation.